Now for Something Completely Different:

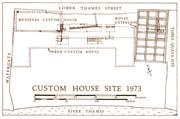

Custom House 1973 CUS73

Gustav Milne

The amalgamation of the London and Guildhall Museums was long in the planning, but only formally completed in the summer of 1975.

Consequently from late 1972, the Guildhall Museum had to shoulder the burden of rescue archaeology in an increasingly redeveloped City during the transition period, and it rose to the challenge. Its offices and displays were temporarily accommodated in Gillet House, a modern building accessed from the High Walks (mostly now demolished) that once graced the brave New World of post-war London. It lay between two significant landmarks. To the south was the City’s municipal office block, on an upper floor of which was a works canteen for corporation employees - this later included its own archaeologists if they took their boots off. To the north, over the elevated walkway, was the Plough pub where diggers celebrated Fridays and Xmas.

By 1973, the Guildhall Museum had already launched a major archaeological rescue programme. Work started in July, for example, on Wool Quay, between the 19th-century Custom House and the Tower, in the heart of what was once the bustling Pool of London. Following the dramatic closure of London’s enclosed docks in the late 1960’s, now redundant warehouses in the upriver port such as those on Wool Quay were being demolished.

By 1973, the Guildhall Museum had already launched a major archaeological rescue programme. Work started in July, for example, on Wool Quay, between the 19th-century Custom House and the Tower, in the heart of what was once the bustling Pool of London. Following the dramatic closure of London’s enclosed docks in the late 1960’s, now redundant warehouses in the upriver port such as those on Wool Quay were being demolished.

The investigations hoped to find the medieval buildings where one Geoffery Chaucer once worked. According to John Stow, the esteemed London chronicler, it was in 1382 that John Churchman “newly built for the quiet of merchants a house on his quay called Le Woole Wharf”. The building served for the weighing of wool in the port of London, so the King’s taxes could be calculated and collected. The chalk arched foundations of this historic building were indeed subsequently exposed and recorded beneath the modern basement floor, to the delight of the museum’s medieval curator, John Clark.

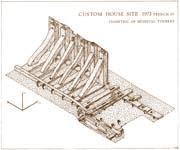

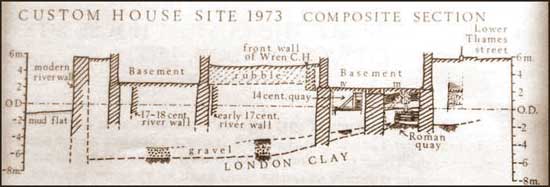

Elsewhere on the site, the remarkable depth of deposit and the network of intrusive modern brick foundations dictated that the site was excavated in a series of deep trenches,  and thus drawn sections were crucial to the understanding the stratigraphic sequence. Well-preserved later medieval timber riverfront revetment structures were recorded, one incorporating an articulated section of a clinker-built vessel. These overlaid the substantial remains of a late Roman wharf structure, comprising large squared oak baulks. All in all, a spectacular site, more than justifying its Guildhall Museum Category 1 status.

and thus drawn sections were crucial to the understanding the stratigraphic sequence. Well-preserved later medieval timber riverfront revetment structures were recorded, one incorporating an articulated section of a clinker-built vessel. These overlaid the substantial remains of a late Roman wharf structure, comprising large squared oak baulks. All in all, a spectacular site, more than justifying its Guildhall Museum Category 1 status.

The Supervisor

This site was supervised by Tim Tatton-Brown, hand-picked by the Guildhall’s still much missed Hugh Chapman, with whom he had dug with in Gloucester way back in 1966. Tim was initially going to work for another summer season in the Mediterranean in 1973, but was encouraged to change his plans, and opt for a site in Lower Thames Street instead. He had previous experience of waterfront sites such as the shipsheds at Carthage and the quays of Knidos, but was nevertheless “surprised” by the depth of deposits in the City, and the associated need for pumps that didn’t break down.

Tim was then studying at the Institute of Archaeology. Its director was the very supportive Professor WF “Peter” Grimes (who had himself spent half a lifetime excavating the City) so Tim also had access to very knowledgeable colleagues and staff. He even persuaded luminaries such as Cecil Hewett, newly appointed to the GLC’s Historic Buildings Division, John Fletcher the dendrochronologist, and even the polymath Stuart Rigold to visit the site, offering invaluable specialist advice and setting the discoveries in a wider context. The on-site team that Tim led included professional diggers, several of whom also went on to work on later excavations in London, such as Peter Ellis, Martin O’ Conell, Jamie Muir and Brian Yule. But there was also a large contingent of volunteer workers, including a committed team from the City of London Archaeology Society, who were clearly appreciated and valued by Tim. Their contribution to this site, and to many others in London in this period, cannot be under over-estimated.

The recording system used by the Guildhall Museum team, with its site note books and sections drawings, differed from the unique-context plan-based matrix-methodology later adopted by the DUA. At the Custom Houses each of the fifteen trenches was given a Roman Numeral Number, and then every layer within that trench, usually visible in the deep sections, was marked with a yellow label, starting from no.1. There were therefore as many layer no. 1s on the site as there were trenches. Finds were collected in trays (one per layer) and were awarded three labels, one for the tray, one for the finds drying out after washing, and one for washed items in a clean bag. Each label was thus inscribed eg CUS73 XII.24. In retrospect -by way of comment not criticism- there was much in the methodology that would have been familiar to Sir Mortimer Wheeler, not least the large number of deep trenches and thus the section-centric records.

Post-excavation work was considered a major priority for the Guildhall Museum. Hugh Chapman ensured Tim was given a desk for a year in the old Guildhall Museum building in Basinghall Street (the DUA would later set up their HQ there) where the site was written up and the drawings produced, all by Tim.

Post-excavation work was considered a major priority for the Guildhall Museum. Hugh Chapman ensured Tim was given a desk for a year in the old Guildhall Museum building in Basinghall Street (the DUA would later set up their HQ there) where the site was written up and the drawings produced, all by Tim.

As the editor of LAMAS Transactions, Hugh also booked slots in the next two annual proceedings, and arranged for specialists such as Wendy McIssac and James Thorne to work on the pottery reports. Other specialist contributions were extracted from mutual friends at the Institute of Archaeology. This glowing example of high-speed detailed post-excavation methodology, was a winning collaboration of a leading museum, several universities and Department of Environment, who held the golden purse strings in those days. The 1973 site was fully published in two parts in 1974 and 1975, a scheduling model few could begin to emulate. The Guildhall Museum certainly set a high bar for future London archaeologists.

MOLA re-excavated deposits on that Customs House site 40 years later, after the 1970s building was demolished. That site, now called Sugar Quay, (SGA12) had a larger budget and a larger professional team than could be mustered in the previous Guildhall Museum era. However, ten years on, the work still remains unpublished (just saying).

MOLA re-excavated deposits on that Customs House site 40 years later, after the 1970s building was demolished. That site, now called Sugar Quay, (SGA12) had a larger budget and a larger professional team than could be mustered in the previous Guildhall Museum era. However, ten years on, the work still remains unpublished (just saying).

The Volunteer

I came from a different background, but had long held an interest in matters historical. Having visited the Billingsgate Bath-house in 1971 (with Chrissie and John) and Baynard’s Castle in 1972, I decided to offer my services to the Guildhall Museum the following year, working on the Custom House site as a volunteer from July 1973 onwards. Only one weekend was missed, when the semi-pro band I sometimes played with had a gig in Rotterdam. When apologies for absence were offered to Tim the following Saturday, he was unimpressed. What in the world could be more important than working down a hole in EC3? He had a point: the only future the band could offer was a short tour of American bases in Europe playing We’ve Got to Get Outa this Place (the ‘Nam Vets anthem) so I subsequently gave up the music for the mud.

If you didn’t bring your own, provisions could be bought at the Italian café near the Tower, affectionately known as the Wop Shop (sorry). There was a real sense of communal purpose on these early “rescue” sites, and the chatter at lunch was often informative, whether on site or in The Tiger pub in the Bowring Centre. The Future of London’s Past had just been published: the talk often turned to what might happen next, or what might the mythical Museum of London actually be? And, when the advert for a new Chief Urban Archaeologist was published in August, who might that be? Peter Marsden? Hugh Chapman? Tim?

If you didn’t bring your own, provisions could be bought at the Italian café near the Tower, affectionately known as the Wop Shop (sorry). There was a real sense of communal purpose on these early “rescue” sites, and the chatter at lunch was often informative, whether on site or in The Tiger pub in the Bowring Centre. The Future of London’s Past had just been published: the talk often turned to what might happen next, or what might the mythical Museum of London actually be? And, when the advert for a new Chief Urban Archaeologist was published in August, who might that be? Peter Marsden? Hugh Chapman? Tim?

Knowledge was willing shared, and it was from the diggers on such sites I learned to identify basic DR forms of Samian pottery as well as the ubiquitous green-glazed medieval wares. In those days, volunteers would take home souvenir unstratified pot sherds recovered from the spoil heaps. But first they had to be shown to the all-knowing Tim before they could be removed from the site, a task he undertook with endless unpatronizing patience.

Anyway, this was 1973 and the economy was not doing well: I subsequently lost my desk-based day-job in November. But I reported to the Custom House excavations the very next day, and was given a short term contract to help the small remaining team wrap up of the site. Apparently well-honed skills of wheel-barrowing, bucket carrying, pick-axeing and hand-sawing of (many) dendro samples served in lieu a CV. However, I still had to master the art of shovelling into a barrow from a distance, without broadcasting the spoil over a wide area. This was crucial, since a trench had to be emptied directly over an adjacent one in which another archaeologist was trying to complete a section drawing. Thanks to the patience of my new colleagues, the required wrist action was mastered by the end of the day, to the relief of a cross draughtsman. I then learned to shovel straight into a barrow 2m above my head with no overspill (not sure if they teach you that in MA courses these days).

Those five months changed my life, and I am forever deeply grateful to Tim and the Guildhall Museum for the opportunities they offered. And what a site to introduce anybody to urban rescue excavations and to Roman and Medieval waterfront archaeology. One of the volunteers commented “..enjoy it while you can, not every site is as good as this”. The crazy thing was that the next generation of riverside sites were, in fact, just as good…..

Comments powered by CComment